I said nice things about this smart WSJ story yesterday about how mail-order pharmacies are soaking employers and patients. Antonio Ciaccia at 3 Axis Advisors then pushed out his report that provides the basis for the WSJ reporting, and it’s worth the read.

Milliman put out a smart and important PhRMA-funded analysis yesterday that explains why more than 3 million Medicare beneficiaries may see their drug costs go up in 2026, even though they’re talking medicines that might be price controlled.

PhRMA has a release and a blog post on this that gets at the topline finding: 3.5 million Part D beneficiaries who take price-controlled meds could see their out-of-pocket spending rise.

But it’s a little counterintuitive, so I want to drill down on why this is happening.

Bear with me for a sec. There’s some math:

This phenomenon stems from a couple of intersecting elements of the IRA. First, there is a $2,000 out-of-pocket cap. This is the one piece of the IRA that everyone likes, and it is, on its surface, super-simple: as soon as a patient spends $2,000 out of pocket on Part D drugs, poof, they’re done. No charge for any additional spending in Part D.

The twist is how that $2,000 is calculated, because it is not necessarily the patient’s actual OOP cost.

Instead, the OOP is calculated on what the patient’s cost burden would be if the standard Part D benefit was used. That means a $590 deductible and 25% coinsurance based on the list price of the drug. Again, that’s pretty straightforward.

But some patients are in Medicare plans with slightly different designs, and those patients may pay less than 25% of the list price of the drug. For many, they have a simple copay — likely because they’re on a medicine that has a lot of competition and big rebates (the market at work!).

But rather than counting the copay amount toward their $2,000 cap, Medicare gives them credit for 25% of the list price.

Consider a medicine that costs $750 a month. The coinsurance runs $187 (that’s 25% of $750). But if a patient is on a plan with a copay, they’ll be paying less. (In Milliman’s examples, they use a $47 copay, so I’ll stick with that number.)

That means that after the deductible is satisfied, every patient gets $187 “credited” toward the $2,000 cap, even if they’re spending way less than that. For the hypothetical $750 drug, the cap gets hit in about September. That’s great news for the $47 copay folks: after less than $1,000 in spending, they’re done. They don’t have to pay for the last three months of their med.

But imagine that the price of that medicine is cut, via the IRA, to $250. That’s good news, on paper, but it ends up screwing the $47 copay folks.

Now, instead of getting a $187 credit each month, the copay beneficiaries only get a credit for $63 (25% of $250). That means that the $2,000 cap never gets hit, and the patient is on the hook for monthly copays that last the whole year. They don’t get a three-month reprieve. They end up spending more for the “cheaper” drug.

So the government gets a lower price on the medicine, but the patient’s burden actually increases.

Milliman makes clear that this isn’t going to happen to everyone. But — still — the idea that 3.5 million people may be paying more for their meds after the IRA than before is a little mind-bendy.

And this is not, presumably, what the drug-price warriors had in mind when they pushed through the IRA.

When the New York Times puts something on A1, it’s worth paying attention. But this is not a squib about the PBM story … the Times ran this obesity story — about the lack of coverage at the state level — on the front page.

It’s good journalism, full of sage quotes that detail the challenges. But it’s unfortunately silent on the underlying economics. These medicines are a good deal and the prices are falling, and we need a real and creative dialogue about where we can find the budgetary headspace to make these more broadly available.

The NYT didn’t provide any of that.

Naturally, I’m fixated on the one graf that did talk money:

West Virginia’s program for public employees was limited to a little over 1,000 people, but at its peak — despite rebates from manufacturers — it cost around $1.3 million a month, according to Brian Cunningham, the agency’s director. Mr. Cunningham said that if it were expanded as intended to include 10,000 people, the program could end up costing $150 million a year …

The math here — $1.3 million for 1,000 patients, $150 million for 10,000 — assumes that these meds cost around $1,300 a month. But that’s not right. Not even close. Zepbound’s list price is substantially lower than that. The net price is at least half of what West Virginia officials suggested to the Times. Probably a lot more.

I’m not suggesting anyone is being disingenuous here. This stuff is pretty far in the weeds. And I don’t want to imply that tough choices disappear if we’re talking $50 million rather than $150 million.

Still, the numbers do matter.

While we’re talking numbers, I’m fascinated by this Hill piece on the effort of Sen. Jacky Rosen to get HHS to explain why in the world Medicare is paying PBMs $3,000 a month for abiraterone when Civica will sell it for $160. And Rosen actually left an ever bigger opportunity on the table: she could have involved Mark Cuban — who sells the stuff for 33 bucks — and received even more attention.

Modern Healthcare looked broadly at the 340B battle in the states, where legislatures are passing bills limiting the ability of manufacturers to put conditions on their dealing with contract pharmacies and courts are dealing with the industry’s pushback.

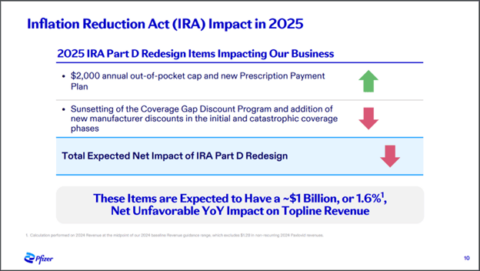

A whole bunch of conservative groups wrote a big letter to Republican congressional leaders detailing their beef with the IRA — mostly around growing premiums — pushing for some sort of action. But it’s not clear what that action might be, and even the letter-writers seem to be unclear on what the long game might be. Axios had the scoop.

Amgen told the federal court overseeing its challenge of the Colorado PDAB program that the underlying law is “unconstitutional for at least four reasons,” per Endpoints.

Header image via Flickr user morebyless.

Thanks for reading this far. I’m always flattered when folks share all or part of Cost Curve. All I ask is for a mention or tag. Bonus points if you can direct someone to the subscription page.