Minnesota 340B Watch Update. I emailed the nice folks at the Minnesota Department of Health about where their 340B transparency report, and I quickly received a brief reply: “We hope to release the report soon.”

So there you have it. It’s coming “soon.” It appears that, like most deadlines, the Nov. 15 date was something of an aspirational target.

Yesterday, I wrote about how the nomination of Robert Kennedy** was going to scramble the way that we think and talk about value.

My thesis was that Kennedy is uniquely placed to accelerate two existing trends: one in which patients will be pushed to make more decisions about their own care without incentives or expert guidance, and another in which patients will be directly paying for more of their own care.

It’s a modern update on the old “skin in the game” conversation,*** in which patients are forced to make complex decisions about both health and finance — drug “value” — with limited resources.

All of this leads to a reasonable question: What can industry do to help patients in this emerging world?

I’d suggest that there are three core elements:

Define value to patients. Traditionally, industry has thought about “value” in a way that was driven by how payers think about value: narrowly focused on clinical outcomes and cost impacts.

Patients see value much more expansively, in ways that aren’t often captured by the usual value elements. Productivity is important to patients. So is impact on caregivers. Option value — the idea that part of the value of today’s breakthrough may make it possible for you to be around for tomorrow’s — is hugely important in some areas, such as cancer.

At some point this week, I’m going to talk about this paper, which gets into all of the different ways to think about value. Increasingly — as an industry — we’re going to have to grapple with how we explain different kinds of value to patients directly, based on what’s important to the patient.

I’m not naive: there are legal, regulatory, and communications challenges in doing so. But just because it’s hard doesn’t mean it won’t be needed.

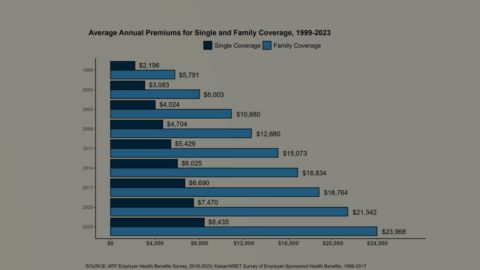

Understand how patients are paying for their medicines. This is 101 stuff for the market access readers, I know, but communicators probably don’t spend enough time thinking about this element, which is hugely dynamic.

Some patients are likely to be far more likely to be exposed to drug prices, and that will change by the kind of medicines they need and the kind of insurance they need. There are plenty of Medicare patients who are benefiting enormously from the new out-of-pocket cap, even as patients on commercial plans face down ever-growing formulary exclusions list.

Not every patient will have to weigh value in the same way, but we can — and must — try to assess how each patient is handling these costs.

Build and promote creative solutions. The last couple of years have seen a thousand flowers bloom when it comes to trying to find ways of delivering high-value solutions to consumers who have to consider the value of their care.

This ranges from brand-name drugs launching with an entirely cash-pay model (Brenzavvy for diabetes), medicines that have essentially tiered pricing for cash-pay customers and those whose insurance will cover (neffy for anaphylaxis), and special cash-pay options for certain types of medicines (GLP-1s in syringes at LillyDirect).

Each of these efforts is an acknowledgment that there is an alternative system in which patients have a huge amount of responsibility for both clinical decisions and financial decisions, and the future is going to belong, in part, to those who can come up with creative solutions … and explain how, when, and why they work.

Here are the paragraphs of caveats: this new world won’t appear everywhere all at once. It’ll probably hit chronic diseases before it hits oncology. Vaccines will be impacted before rare diseases. Commercial patients might be exposed before Medicare patients. And this is likely an evolutionary process, not something that will simply appear one day in its full form.

Maybe Kennedy will be a catalyst for these changes, or — perhaps — he’ll be uninterested in championing or unable to promote reforms that would more quickly foist value decisions on consumers.

But it’s hard not to think this is where we’re headed, directionally, and it would behoove every brand communicator to begin thinking — if only in a “scenario planning” sense — for what Kennedy may bring.

** Standard disclaimer: the nomination remains a bad and dangerous idea, and my musing on strategery ought not be taken as a signal that the nomination shouldn’t be opposed by anyone who believes in science as a process.

*** The idea that consumers do better when they have “skin in the game” is objectively wrong, and I don’t want anyone to think that I’m advocating for that here.

Here’s a buffet of comments about benefit design that come from the Fierce Payer Summit conference. You ought to skim the whole thing, if only so you reach the end, which has a wild quote from Ed DeVaney, president of employer and health plans at CVS Caremark:

“When you look at our acquisition price and what we’re selling it to customers, after you get rid of this cross-subsidization, which is again losing money on every brand, making up more than your fair share on generics, Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs is 40% more expensive,” he said at the conference.

I know the underlying point has merit — soaking those who purchase generic drugs at outrageous markups may indeed, in theory, allow for lower costs elsewhere — but DeVaney’s word-salad version underscores how uncomfortable the shell game reality is for PBMs.

ELSEWHERE:

I love this WSJ story on Lilly’s effort to court employers specifically around obesity-med coverage. Employers are where the buck stops, and the better they can understand what they’re buying, the better off employees will be.

AIR340B published a worthwhile new memo on 340B spending by Dan Crippen, who used to run the Congressional Budget Office. It makes the point that the out-of-control growth of the 340B reduces government tax revenue by about $14 billion via wealth transfer from taxable groups (pharma) to tax-exempt organizations (nonprofit providers). This is in addition to the well-established ways that 340B drives up prices by encouraging the use of more expensive medicines and accelerating consolidation, which Crippen also calls out.

Ian Spatz from Manatt has been watching DC for a long time, so I’m inclined to believe his take on just about anything. Here’s what he’s expecting out of the next four years.

This Axios piece makes the case that Republicans don’t have a play on drug pricing. Sure, they can do stuff, but nothing that will actually make much of a difference.

I can’t vouch for the rigor of this poll on consumer attitudes around PBMs from Navitus (is an online “Pollfish” survey credible? I have no idea), but I’ll vouch for the interestingness of its findings. Most eye-catching — though probably not surprising — was the data on awareness of PBMs. Three in four of those polled didn’t know what a PBM was, and nearly nine in 10 had no idea which PBM was covering them.

Thanks for reading this far. I’m always flattered when folks share all or part of Cost Curve. All I ask is for a mention or tag. Bonus points if you can direct someone to the subscription page.