I know there are some new readers today, and, in the interest of expectation-setting, I wanted to reassure them that the newsletter isn’t usually this long. But I’ve been thinking about how Roche talks about value — see “The Arc,” anon — for a couple of weeks now, and I wanted to share that journey with you.

Since the IRA was passed, people have been screaming to the rooftops that the law — almost certainly unintentionally — creates a huge disincentive to develop cancer drugs.

Oncology medicines tend to be developed in a careful, stepwise manner: they’re approved first for patients who have run out of other options and, over time, garner earlier-line approvals. That means that price controls that are timed to the very first approval give companies a short window to do all of that follow-up work.

This feels like a self-evident fact, but the lack of a consensus that a fix is needed means that this fact needs more support and more amplification.

This is why I was happy to see Health Affairs publish a rigorous analysis of oncology drug development over the past 20 years that makes clear exactly how much post-approval work is being done: almost 70% of research and more than half of all indications happen after that first FDA approval.

It’s that kind of research that is explicitly threatened by the IRA, and it’s good to have that documented.

I spend a lot of time around here talking about the importance of “value communications.” It’s the idea that the biopharmaceutical industry can and should explain how its products are a good deal for society, defining what a “good deal for society” means.

It’s not easy, in part because there’s a natural skepticism around the industry and in part because concepts around value/reimbursement/access aren’t necessarily intuitive.

So I’ve always been impressed with companies that try to sort this out and fascinated by how they frame the arguments. So today I want to talk about how Roche has been thinking about the topic over the past half-decade or so. (Roche isn’t/hasn’t been a client, and all of this is in the public domain.)

Each year, in the early autumn, Roche holds a big meeting for its investors known as “Pharma Day” where the company walks through its entire business — 100+ slides of commercial approach, pipeline detail, clinical summaries, and the like. And, since 2019, they’ve sought to include pricing details.

Here’s how it looked in 2019:

The company was trying to tell three different narratives, one about its international approach, one that emphasized net prices, and a brand-level story that suggested that pricing low could drive commercial success.

The latter concept was somewhat novel: companies sometimes, but not often, launched at discounts to their competitors, but I can’t think of another company that celebrated it as a strategy.

***

In 2020, Roche blew out the story a bit more:

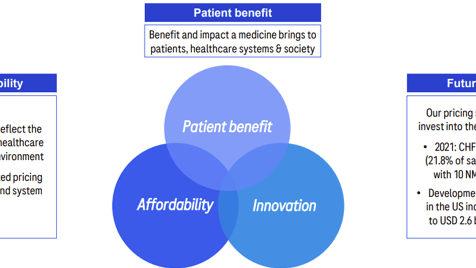

Here, the company kept two of those core narratives, including the discussion around the branded approach. But expanded its pricing vision by providing a philosophical framework that was based on the WHO’s definition of fair pricing, which picked a well-validated definition that allowed the company to talk about the balance between price and innovation.

And they looked at the idea of value — “costs to society” — by emphasizing ways that their medicine delivered cost savings to the system and patient quality of life benefits.

***

In 2021, Roche pared back its approach:

Here, access was folded into a broad ESG framework, with the gross-to-net chart making its third straight appearance. But the more detailed thinking on value was lost, at least temporarily.

***

2022 brought back some of the compelling content from previous years:

The WHO “fair pricing” definition returned, along with some stats showing Roche’s spend on innovation and making explicit the tie between commercial success, access, and the ability to deliver innovation.

The gross-to-net chart remained, and a box full of branded examples reappeared as part of the slides, with an additional two examples.

***

Roche returned to a slimmed-down version in 2023:

The brand box again made the presentation, with a new branded example. And the gross-to-net chart, too, was included, along with a boast that the IRA’s provisions for penalizing companies that hiked prices faster than inflation wouldn’t touch the company.

***

The 2024 presentation took place a couple of weeks ago, and pricing had been whittled away to this:

The Ocrevus pricing approach — a staple of Roche’s slides since 2019 — was still there, but everything else had disappeared.

***

I understand the 2024 omissions. The gross-to-net story is getting more complicated across the industry, and I suspect that graph might have told a more nuanced story in 2024 than it did a year or two ago.

But industry ought not shy away from that complexity. In a similar vein, I was sad to see the WHO “fair pricing dimensions” fall out of the talk track. Having a well-defined philosophy is never a bad move.

To be clear: I don’t know anything about the choices Roche made here. It’s possible that they believed that the stories weren’t as compelling as they were. Or that investors didn’t really care. Or that Pharma Day had other priorities. Or that we’ve moved past the moment in time where transparency around value and pricing was table stakes.

Whatever the reasons, I’m rooting for a resurrection of the value discussion in Roche’s presentation next year. There’s no evidence that Roche’s commitment to value has waned, and it would be good to see continued attention here.

More broadly, I liked the Roche Pharma Day value/pricing mentions for the same reason that I celebrate the Janssen and Sanofi transparency reports. It showed to audiences well beyond investors that pharma isn’t afraid to have these discussions.

And that’s where the real value of the effort — pardon the pun — lies.

This Oregon PBM transparency report is terrible. On the surface, it shows how much of the rebate dollar is passed to plans, but that hardly tells the whole story. “Rebate” is a slippery concept, and PBMs have created all kinds of workarounds to ensure that steady stream of revenue remains with the PBM.

The reaction here has been telling. Adam Fein has declared the effort to be “GIGO,” and 46Brooklyn’s Antonio Ciaccia mused, “I’ve always believed that any information is better than nothing, but I’m not sure how much better than nothing this is either.”

On the flip side, Harvard PORTAL’s Ben Rome went all-in on praising the Oregon effort, which is … weird. Right? Like, being a pharma skeptic shouldn’t automatically make one a PBM apologist, but here we are.

Elsewhere:

There is no one who understands the public health impacts of health benefit design better than Michigan’s Mark Fendrick, who has a Real Clear piece out today highlighting one of the IRA’s many strange elements: the way that out-of-pocket spending may rise between 2025 and 2026 for seniors taking price-controlled medicines.

I’m low-key fascinated by a California ballot measure that seems to be about 340B but is actually about rent control. I’ll say more about this later, but it’s noteworthy that the ballot measure, whatever its true purpose, is structured around ensuring that 340B profits are linked to patient benefit.

When John Arnold speaks, I listen. Today, he and Laura Arnold are talking site-neutral payment reform in a STAT op-ed

Thanks for reading this far. I’m always flattered when folks share all or part of Cost Curve. All I ask is for a mention or tag. Bonus points if you can direct someone to the subscription page.